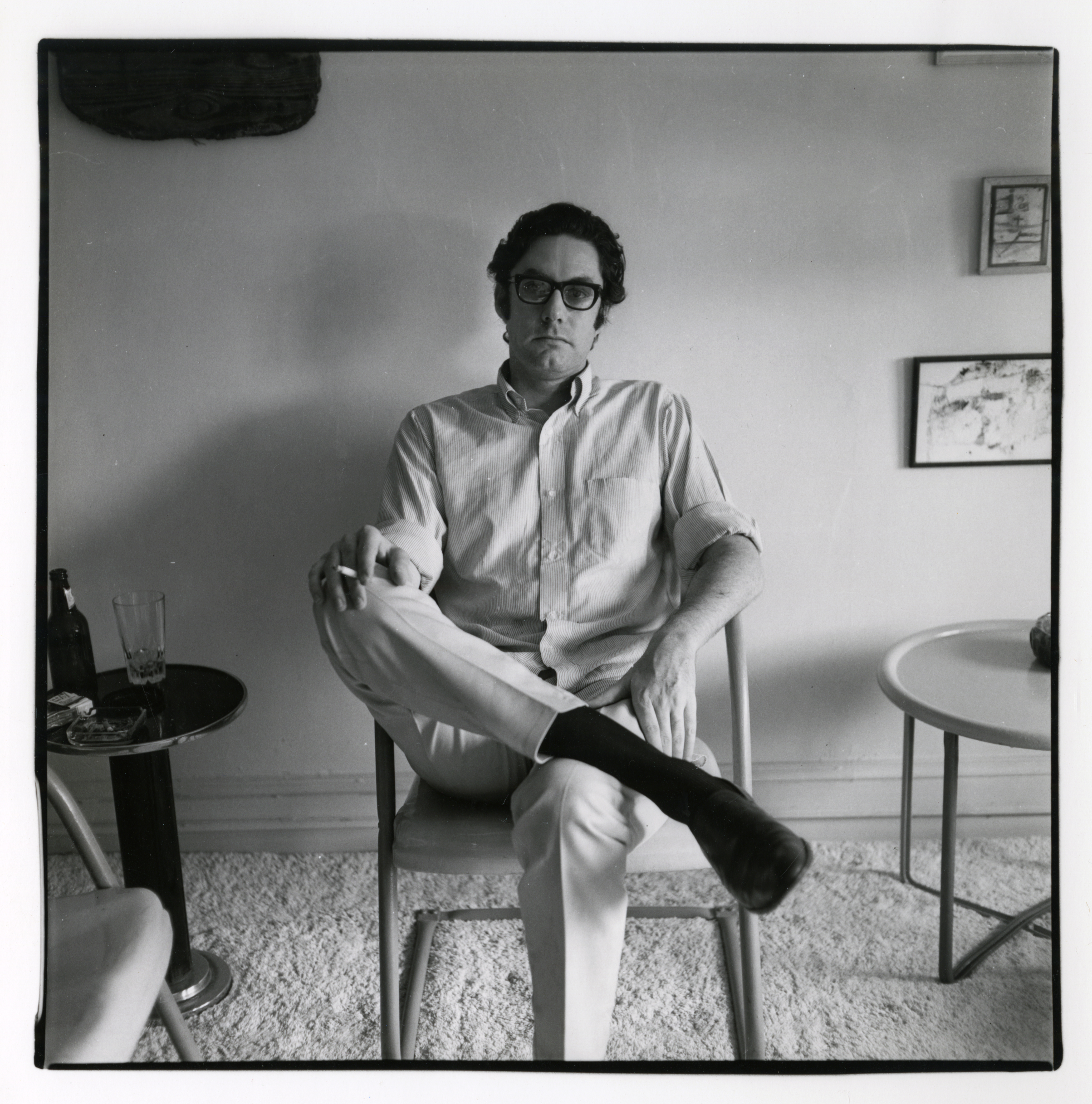

Walter Hopps, in Washington, D.C., in 1978. Photograph by William Christenberry. Collection of William Christenberry.

Walter Hopps’s just-published memoir, The Dream Colony, opens with the sentence “My parents collected plein-air California paintings, and that was the art that hung in the Hopps household.” The line is striking for its thumbnail sketch of the pattern Hopps’s life would take: that he managed to turn identifying, collecting, and living with art into a career that vastly influenced post–World War II American art. As a teenager in Los Angeles, the precocious and curious Hopps regularly visited the great collectors and Duchamp supporters Walter and Louise Arensberg and explored the museums and galleries of LA; by night he soaked up the city’s jazz scene, where he befriended Chet Baker and a young Dave Brubeck. In 1952, at the age of twenty, he opened a gallery, Syndell Studio, and, three years later, mounted an exhibition called “Action” in an empty carousel on the Santa Monica Pier. The show introduced both an aesthetic and a group of artists that would engage Hopps for the length of his career: gritty assemblage and abstraction as exemplified by Jay DeFeo, Hassel Smith, and Craig Kauffman.

With the sculptor Ed Kienholz, Hopps opened Ferus in 1957. It became the ur–sixties Los Angeles gallery, home to the young artists Wallace Berman, Ken Price, and Billy Al Bengston, among others, and host to Andy Warhol’s first West Coast solo show. Hopps, however, was never very comfortable as an art dealer, and in 1962 he became the curator of the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum of Art), where he gained fame and critical attention for shows that were the first of their kind in the United States, including Marcel Duchamp and Joseph Cornell retrospectives and the country’s first Pop Art overview, “New Painting of Common Objects.”

From the midsixties through the seventies, Hopps served in leading curatorial roles at the Washington Gallery of Fine Art; the Corcoran Gallery of Art, where he showed artists as diverse as Walker Evans and Robert Crumb; and the Smithsonian’s National Collection of Fine Arts, where he mounted a Robert Rauschenberg retrospective and began a friendship with the artist that lasted the rest of his life. In 1980, Hopps began collaborating with the collector Dominique de Menil as a consultant to the Menil Foundation in 1980, and in 1987 the Menil Collection opened; he was its first director, and then its curator of twentieth-century art. Hopps was made adjunct senior curator of twentieth-century art at the Guggenheim Museum in 2001.

In 1990, he joined Jean Stein’s Grand Street as art editor. It was there that he began collaborating with the magazine’s managing editor, Deborah Treisman, and the assistant art editor, Anne Doran, on art essays for the magazine and catalogue essays. A few years later, the three began work on his memoir. I corresponded with Treisman, the fiction editor of The New Yorker, about the process behind the book and the particular talents of its subject.

INTERVIEWER

When did you come to this project in its current iteration?

TREISMAN

I didn’t actually “come to the project,” I was part of it from the conception. At Grand Street, Walter selected the artists whose portfolios appeared in the magazine and often provided the accompanying text. He wasn’t particularly comfortable writing—he was far better at speaking and storytelling—so usually we would talk on the phone, or he would talk onto tape, or he would be interviewed by Anne, and I would turn those conversations into the essays that ran alongside the visuals. We went through the same process to put together catalogue essays for some of the major exhibitions Walter curated in the nineties. At some point, after I had moved to The New Yorker, we started discussing the idea of doing a larger project, a book that wasn’t a direct autobiography but that would cover most of Walter’s life and the many artists he wanted to talk about. I wrote up a proposal for the book, which Bloomsbury USA acquired, and Anne was on board to do the interviewing. She had known Walter for decades and was familiar with many of his stories and with much of the work he’d done, so she was able to guide him and keep him focused on the project, which wasn’t always an easy task. Walter had a tendency to digress!

Anne would fly to Houston and spend a few days at a time prodding, encouraging, questioning, and taping. When she came back to New York, she’d hand over the tapes, and I would then listen and transcribe whatever seemed useful, turning it into more coherent sentences and paragraphs as I went and ignoring whatever wasn’t relevant to the book—so there are no direct transcripts of the tapes, as such. There’s no particular chronology to them, either. Walter would jump around in his life, talking about events from completely different times and places in the same five minutes. He’d tell the same anecdote several times in different ways but skip over time periods and artists he probably did want to address. The idea was that I would unravel, rearrange, and rewrite all of this to put together a manuscript, which we could then go over together, and that I would be able to ask him to fill in the gaps, once we could see what they were.

Unfortunately, Walter died before we reached that point. If I remember correctly, he’d seen a draft of only about the first fifty pages of manuscript, dealing with his childhood and youth. After that, some of the steam went out of the project for me. It was dismaying to think of moving forward without Walter. Plus, I’d recently had my first child, I’d been promoted at The New Yorker, and finding time to form a cohesive narrative from a hundred hours of disconnected audiotape was a challenge. But, stealing a week or two here or there, and drawing on some supplementary materials—other interviews Walter had given, primarily—and doing a fair amount of research to try to work out which of the several versions of each story was the most accurate, I eventually managed to come up with a manuscript that felt right to me, or at least representative of Walter, his voice, his thoughts, and what he’d wanted to convey, if not exactly the book we would have been able to do if he were still around.

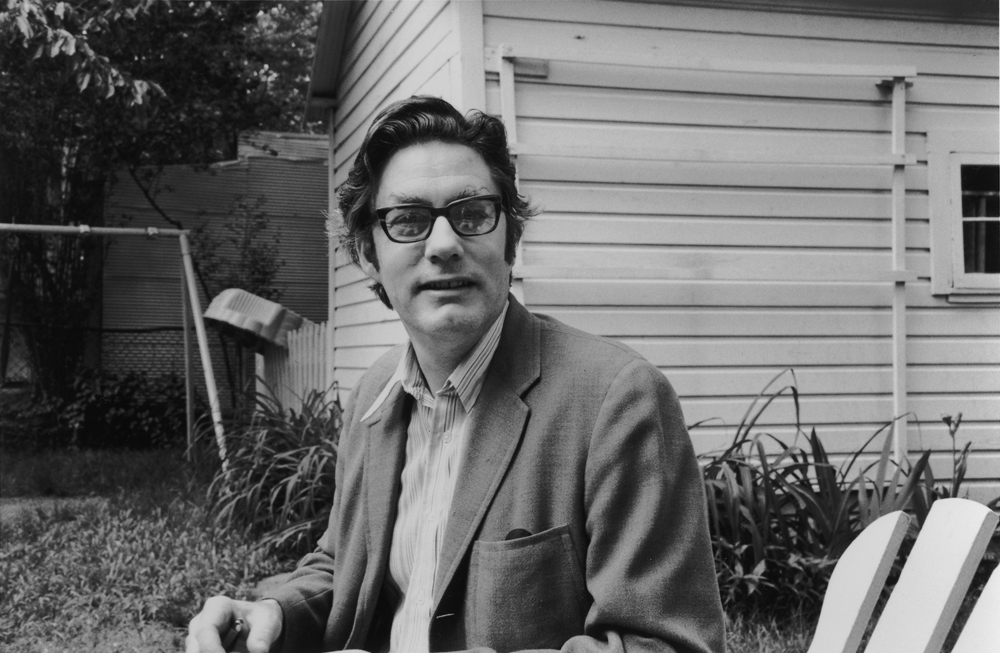

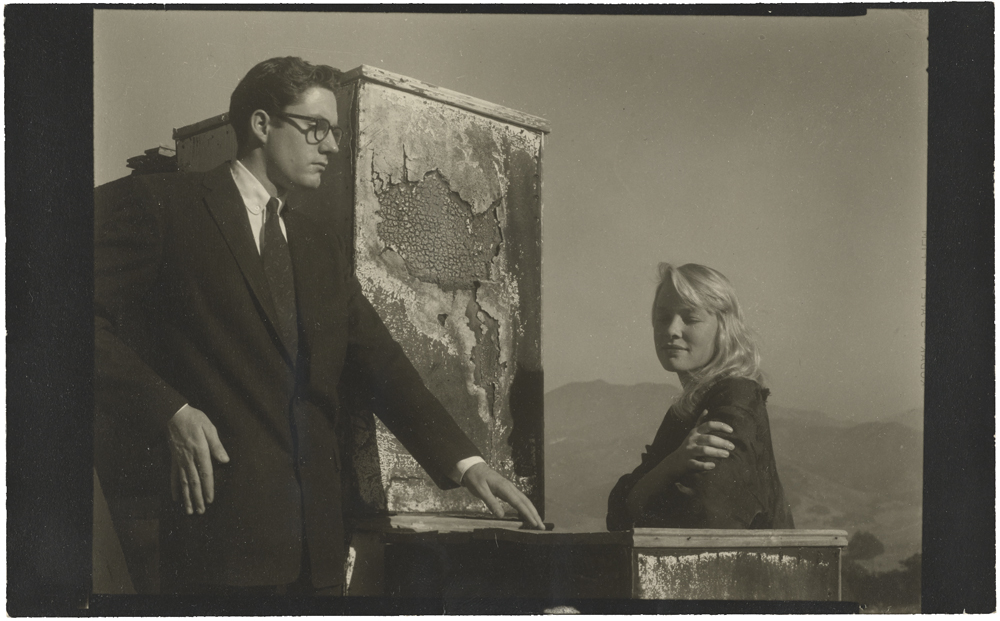

Walter and Shirley Hopps at Ice Boxes in Malibu, California, 1955. Photograph by Edmund Teske. The J. Paul Getty Museum. © Edmund Teske Archives/Lawrence Bump and Nils Vidstrand.

INTERVIEWER

Walter’s digressions seem like both a strength and a weakness. On the one hand, his digressive spirit let him follow multiple strands of art at once. On the other, they became an impediment to finishing this kind of project. What was it about writing, do you think, that he resisted? Aside from being digressive by nature, I mean.

TREISMAN

Oh, I don’t think his digressions were an impediment to finishing this project. His digressions are part of what make the book interesting and give it color. The only real impediment, on his part, was the fact that he died before we’d had time to finish.

As for writing, he had a tendency to sound academic or stilted when he put words on a page, and he’d lose the narrative flow that was so integral when he talked. Ruscha talks about how Walter would deliver his monologues while pacing the room—that was how he composed his thoughts. He was a social being, I think, and he needed to say what he had to say to someone, rather than sitting with pen in hand to address an abstract, invisible audience.

INTERVIEWER

While reading his accounts, some notable omissions struck me, in particular his years at the Menil. This couldn’t be helped, of course, but what do you feel is missing that readers should look into further? What do you feel is not accounted for in his own words?

TREISMAN

He seemed to have some resistance to talking about his years at the Menil. Perhaps because it was such recent history for him and therefore less processed. It’s always easier to narrate the peaks and valleys of one’s youth than later years, when life happens on more of a plateau. But someone should write a comprehensive biography of Walter that covers those years. There’s plenty to tell. I also regret that he never got around to putting together a chapter he really wanted to include in the book, which he used to call “los olvidados,” or “the forgotten ones.” He wanted to talk about six or seven artists who had done surprising or unique work and then flamed out, disappeared, died young, and were now forgotten.

INTERVIEWER

Who are some of the olvidados who would have been included in such a chapter?

TREISMAN

Michael Scoles, who was involved with Syndell Studio and later committed suicide. Bradley Pischel, whom Walter knew as a teenager and who turned up later, after having served in the Korean War, and died, possibly also by suicide, in his late twenties. The Reverend Robert Alexander, or Baza, who ran Stone Brothers Printing and later started the Temple of Man. Arthur Richer, the artist, whose work was shown at Syndell, who died of a drug overdose. Charls Tracy, whom Walter thought of as a “pioneer of pattern painting.” Cameron Booth, a Minnesota artist who taught Frank Lobdell. And, I think, also Craig Kauffman, Walter’s childhood friend, whose work was shown at Ferus. There were probably others, too. Most of these people are mentioned in the book, but not in the olvidados context.

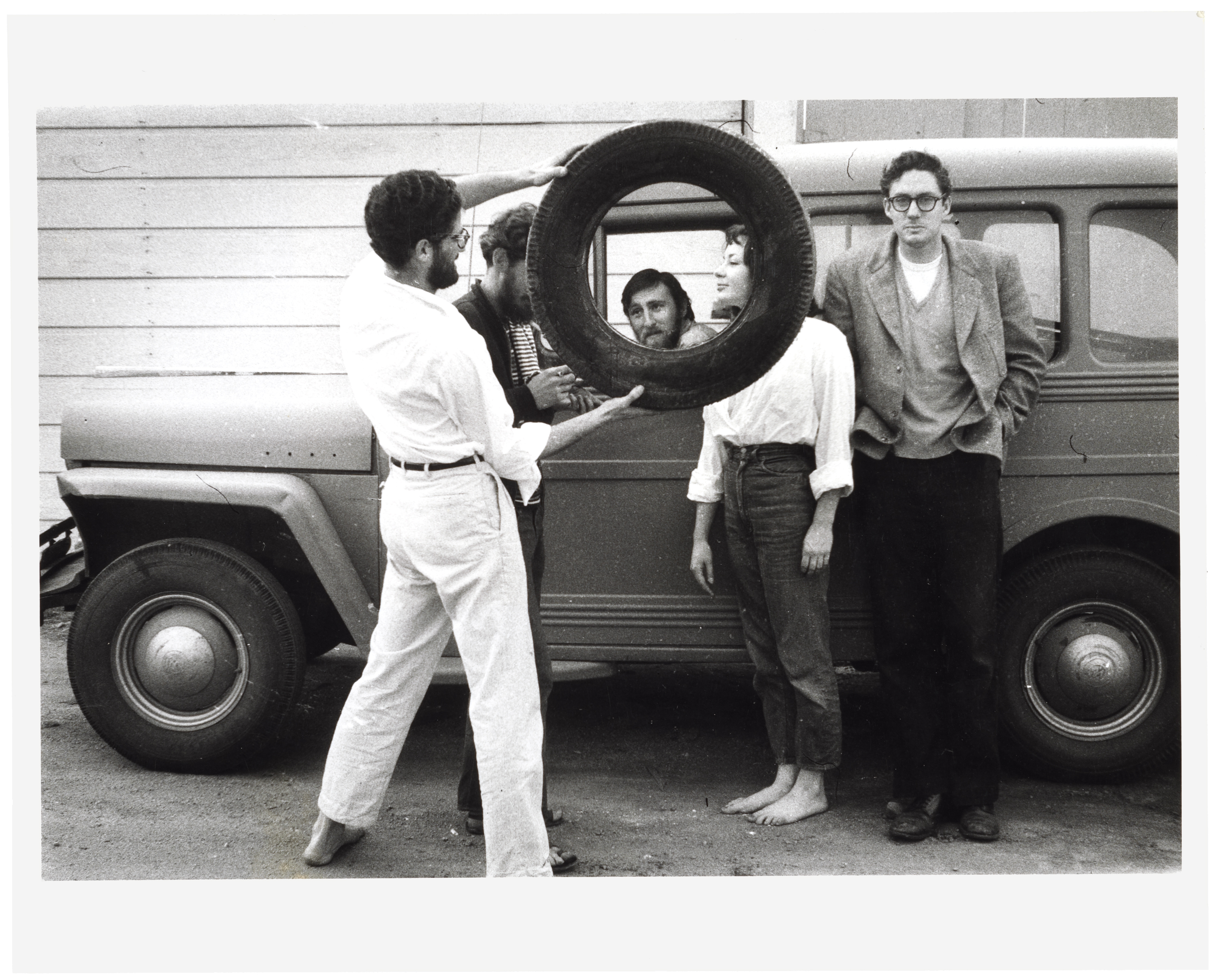

Robert Alexander, John Reed, Wallace Berman, Juanita Dixon, and Walter Hopps in the alley next to Ferus, ca. 1957. Photograph by Charles Brittin. The Getty Research Institute, Charles Brittin papers. © J. Paul Getty Trust.

INTERVIEWER

Walter’s voice comes through rather beautifully, particularly when describing his youth and early twenties, and when talking about Ed Kienholz. He’s straightforward and affectionate about his friends, lovers, and artists. He’s occasionally dark, though, during the various times of financial and physical desperation. Was he ever melancholy about the past? As the book unfurls, he sort of keeps moving, dodging disasters, mounting amazing exhibitions along the way. What do you think he found in the Menil that let him, at last, stay rooted for a while?

TREISMAN

I never heard him express regret or melancholy—except perhaps about his relationship with his father. He certainly had down times in his life, and he struggled with addiction as a younger man, but I don’t think there was a time in his life when he didn’t have the drive to keep going and doing. The world really fascinated him. When the Menil opened, he was in his midfifties, a time at which most people do choose to stay rooted. He also found in Dominique de Menil a real partner, someone who understood art, understood him, and supported almost anything he wanted to do, which wasn’t a relationship he’d often had before. Tom Leavitt at the Pasadena Art Museum and Joshua Taylor at the NCFA were very supportive of Walter but were not always entirely in control of what their institutions could take on.

Going back to the omission of Walter’s later years from the book—the Menil opened in 1987. Walter suffered a brain aneurysm in 1994, and I’m not sure he ever fully recovered his short-term memory. I suspect he had a harder time formulating a narrative of his life after 1994 in part for that reason. His memories from earlier years were pretty much etched into his brain, but the later years would have been more elusive for him as a storyteller, less structured.

INTERVIEWER

The chronology of Walter’s life is striking in that it runs through and beyond minimalism, conceptualism, identity politics, et cetera. He seems, in the book, unengaged with all those theoretical/commercial/curatorial arguments, and yet this doesn’t seem to have hurt him in his career. Did he resist theory? Was he still pursuing the “new” in the eighties and nineties?

TREISMAN

Walter was well-versed in art history, but I don’t think that academic theory interested him much. He wanted to be hands-on with the actual art, rather than engaged in a theoretical discourse surrounding it. If anything, he was more interested in scientific theory than art theory. Yes, he was very much still pursuing the new in the last couple of decades of his life. Check out some of the portfolios that ran in Grand Street while he was on staff there—many of those artists were still early in their careers at that point and later became real stars in the art world. He was also very good at staying in touch with—and listening to—people who were out there on the front lines of art, whether artists themselves or gallerists.

INTERVIEWER

Curators like Hopps simply don’t exist anymore, but to simply say “he had a great eye” isn’t quite enough. How would you characterize his gifts?

TREISMAN

I suppose he approached art in the way an artist would—but without the restrictions of being an artist himself, without the need to commit himself to one particular form or style or question. He could be open to all of it, and he was especially open to the periphery, to the unexpected. I think he saw art not as a historical progression—a series of movements over time, each one leading to the next—but as something that happens, in a sense, all at once, a world in which a Renaissance Pietà exists alongside a Duchamp urinal or a Warhol soup can. Ed Ruscha gets at this in his introduction to the book, when he says that if Walter saw you working with “blocks of red” he’d start talking about Malevich. There was no reason, in Walter’s mind, that a Ruscha work created in Los Angeles in 1965 should be considered separately from that of a Russian artist working fifty years earlier. Walter also came at art from a background in science. His parents and grandparents were doctors. At university, he studied physics and biology, and he later worked as a chemist. For Walter, there was always something sort of forensic or clinical about art, about the actual materials used, as well as their emotional, psychological, or transcendent significance.

Dan Nadel is a writer and curator based in Brooklyn.